Bone stress dates world's oldest walker

Previously it was thought that the first terrestrial vertebrates were small animals from Scotland.

But new analysis of a 333 million year old broken bone suggests otherwise, pushing back the date of the first terrestrial vertebrates by two million years.

The findings came from a big research project by a team from Monash University, Queensland University of Technology (QUT) and the Queensland Museum, which is published in the journal PLoS One.

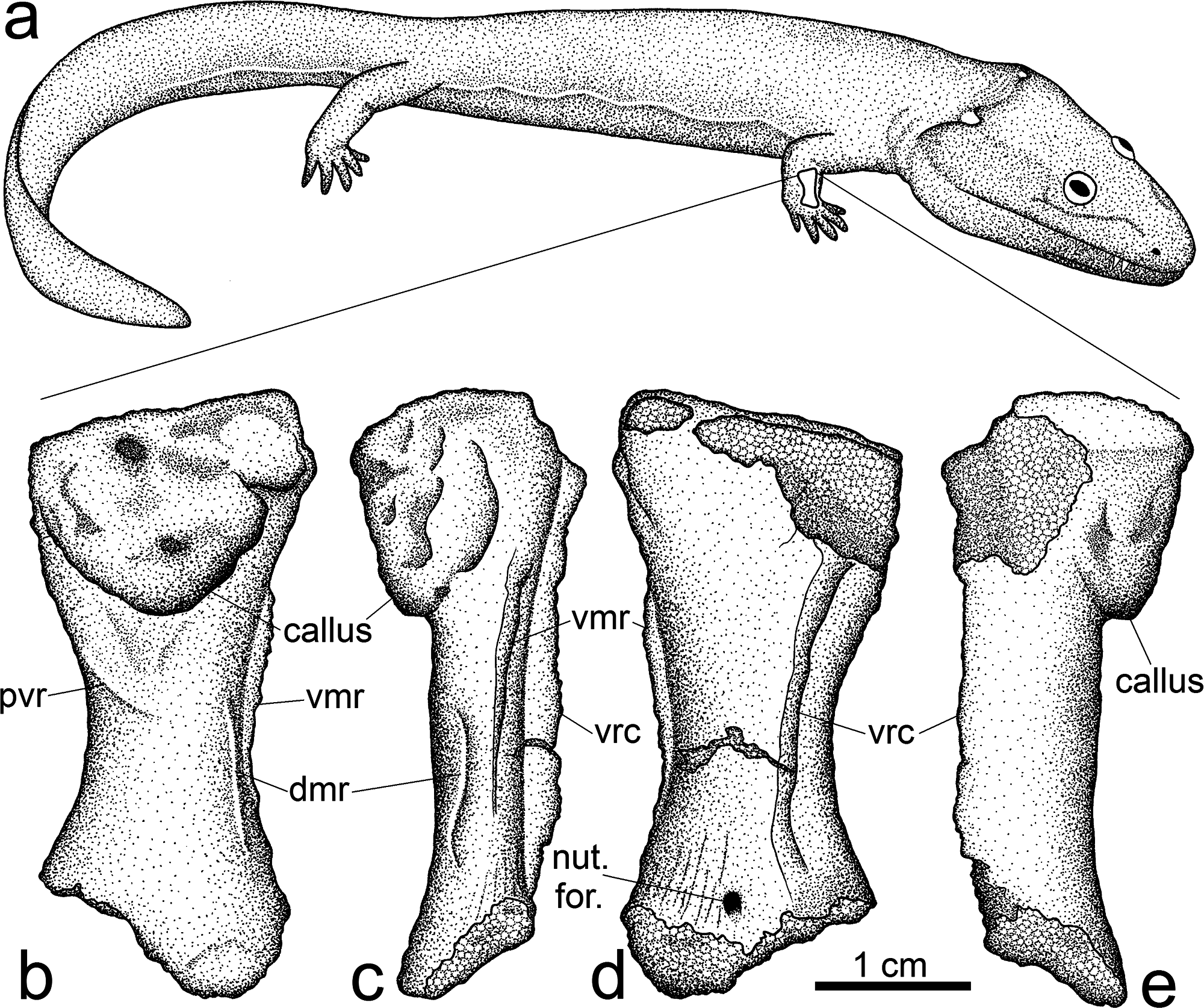

The team studied the fossil remains of a very primitive amphibian, called Ossinodus pueri, which looked something like a cross between a crocodile and a fish.

Significantly older and much larger than the fossils found in Scotland, the Ossinodus was found in 2001 near the central Queensland town of Emerald.

The team took a second look at the fossil using CT scans.

Scans of the 4cm long arm bone - which had fractured in life and had started to heal when the animal died - revealed that its internal microstructure was consistent with an animal that spent time walking on land.

Applying the same principles that engineers use to assess whether a building or bridge is adequately supported, the team developed a three-dimensional computer model of the bone.

They then used engineering software to determine what kinds of forces were needed for the bone to break in a manner consistent with that seen in the fracture.

The simulations indicated that the bone broke under a very large impact force, about five times its own body weight.

The team surmised that a fall on land was the most likely explanation for the broken arm bone.

“This specimen of Ossinodus is our oldest vertebrate ancestor shown biomechanically to have spent significant time on land,” said QUT’s Dr Matthew Phillips.

“It is two million years older than the previous undoubtedly terrestrial specimens found in Scotland.”

The research team found other features that confirmed the tetrapod had spent substantial time on land as well.

The internal bone structure was consistent with re-modelling during life in accordance with forces generated by walking on land. They also found evidence of blood vessels that enter the bone at low angles, potentially reducing stress concentrations in bones supporting body weight on land.

“Other, older tetrapods are known from elsewhere in the world, but it is unclear if they were capable of supporting themselves on land,” Dr Catherine Boisvert from the Australian Regenerative Medicine Institute (ARMI) at Monash University said.

“With Ossinodus, however, we can say with great confidence that this creature was walking on land 333 million years ago.”

The study is published in the international journal PLoS One, and the fossil specimen is housed in the Geosciences Collection of the Queensland Museum.

Print

Print