Fish wave off predators

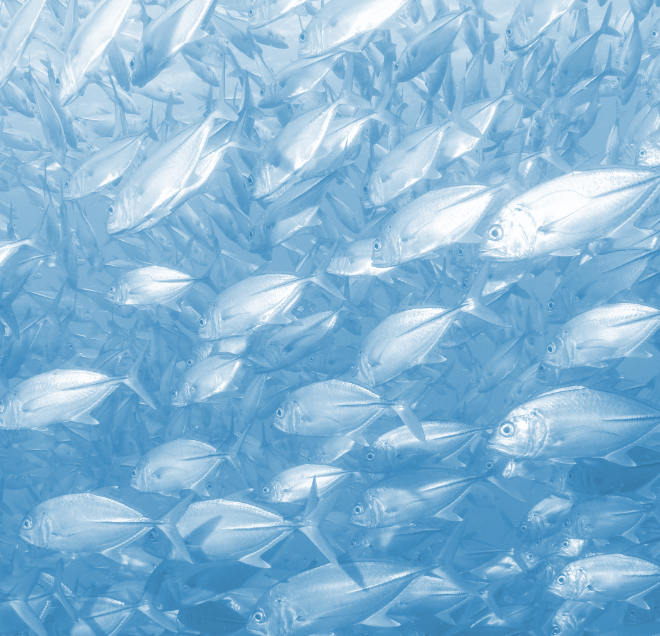

Schools of fish have been shown to protect themselves by performing a group wave.

Schools of fish have been shown to protect themselves by performing a group wave.

In the sports arena, human spectators sometimes create a spectacle known as a ‘Mexican wave’, successively standing up with arms in the air.

Now, researchers have shown that small freshwater fish known as sulphur mollies do a similar thing, and for life or death reasons.

The collective wave action produced by hundreds of thousands of fish working together helps to protect them from predatory birds.

“The surprises came once we realised how many fish can act together in such repeated waves,” says researcher Jens Krause of the Leibniz Institute of Freshwater Ecology and Inland Fisheries in Berlin.

“There are up to 4,000 fish per square metre and sometimes hundreds of thousands of fish participate in a single fish wave. Fish can repeat these waves for up to two minutes, with one wave approximately every three to four seconds.”

These unusual fish are found in sulphuric springs that are toxic to most fish, but the behaviour is hard to miss. The mollies do the same thing in response to a person nearby.

“At first we didn’t quite understand what the fish were actually doing,” said researcher David Bierbach.

“Once we realised that these are waves, we were wondering what their function might be.”

The presence of many fish-eating birds around the river made them think it likely that the fish waving behaviour might be some sort of defence.

They decided to investigate the anti-predator benefits of the animals’ wave action.

Their studies confirmed that the fish engaged in surface waves that were highly conspicuous, repetitive, and rhythmic.

Experimentally induced fish waves also doubled the time birds waited until their next attack to substantially reduce their attack frequency.

For one of their bird predators, capture probability, too, decreased with wave number.

Birds also switched perches in response to wave displays more often than in control treatments, suggesting that they had decided to direct their attacks elsewhere.

Taken together, the findings support an anti-predator function of fish waves.

The findings are the first to show that a collective behaviour is causally responsible for reducing an animal’s predation risk.

As such, the researchers say that this discovery has important implications for the study of collective behaviour in animals more broadly.

“So far scientists have primarily explained how collective patterns arise from the interactions of individuals but it was unclear why animals produce these patterns in the first place,” Dr Krause said.

“Our study shows that some collective behaviour patterns can be very effective in providing anti-predator protection.”

It may be clear that the fish’s waving reduces birds’ chances of carrying out a successful attack on sulphur mollies, but what is not yet clear is exactly why.

The experts say they might get confused, or use waves to tell birds that they have been noticed.

In future studies, the researchers plan to explore such questions.

Print

Print