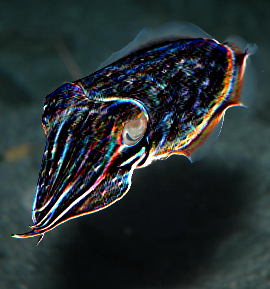

Strange, unique sex lives spied in cuttlefish gut

Ten new species of parasite have been discovered in the kidneys of cuttlefish, and it appears the microscopic bugs enforce strict boundaries on their sexuality.

Ten new species of parasite have been discovered in the kidneys of cuttlefish, and it appears the microscopic bugs enforce strict boundaries on their sexuality.

Some astonishing details of the lives of cuttlefish parasites have been revealed in research by the University of Adelaide.

Researcher Dr Sarah Catalano has described 10 new parasite species − dicyemid mesozoans − which live in the kidneys of cephalopods including cuttlefish, squid and octopuses.

They are the very first dicyemid species to be described from Australian waters.

Dicyemid parasites are tiny organisms, simple in appearance and made up of only 8-40 cells without any obvious tissue structure - but they do have surprisingly complex life cycles.

They exist in two forms: adults are long and slender whereas embryos can be a clone of the adult only smaller, or have a distinctive circular form. They also have two modes of reproduction - sexual and asexual.

“Although dicyemid parasites have been studied by other groups, nothing has been known about dicyemid fauna and infection patterns from Australian waters,” says Dr Catalano.

“Surprisingly, we found that the left and right kidneys of a single host individual were infected independently of each other, with one kidney infected by asexual forms and the other by sexual forms, suggesting this mechanism is parasite-controlled not host-mediated,” she said.

“To make their life cycle that much more complex, these parasites are also highly host-species specific. To infect a new host, the circular embryo form of the parasite is released with the host's urine out into the sea. It then has to find a new squid or cuttlefish or octopus individual that is of the right species within a limited time-frame before it perishes, while also battling environmental conditions such as strong water currents and varying salinity.

“Somehow this tiny organism - just a few cells in size - manages this complex and highly specific reinfection and the astonishing life cycle beings again.”

The bugs are so specific that they may even function as biological markers to help monitor cephalopod populations.

“We looked at the dicyemids in two species of cuttlefish... from various localities in South Australian waters,” Dr Catalano says.

“We found different dicyemid species infected each cuttlefish species at different localities, suggesting there are unique populations of each host species in South Australian waters.”

“As such, this offers support for the use of dicyemid parasites as biological tags and we hope to be able to use these parasites to tell us more about cephalopod population structure to assist in management plans,” she said.

The incredible and somewhat bizarre life of dicyemid fauna is detailed in the paper published by the journal Folia Parasitologica.

Print

Print